"Investigators focused on literary works" intensify their pursuit of assets belonging to Jewish owners, misappropriated during Nazi rule.

Following the conclusion of World War II and as the atrocities of the Holocaust came to light, the emphasis shifted towards recognizing the human toll, seeking justice, retribution, and providing answers for the survivors and bereaved families.

This period also marked the emergence of initiatives that aimed to provide reparations and restitution, not just for the immense torment inflicted but also for the properties seized by the Nazis.

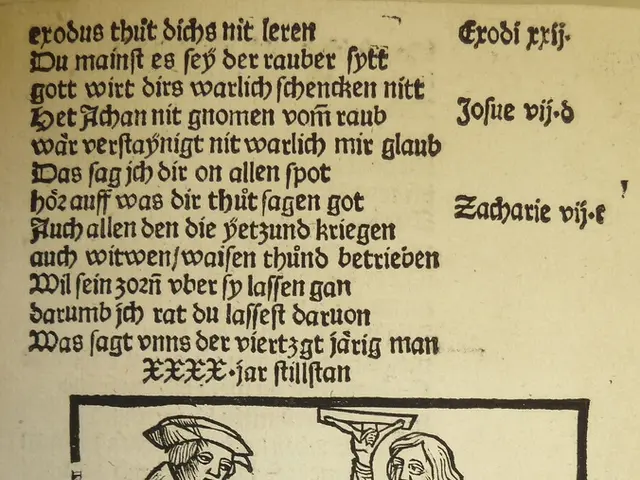

The media often highlighted the theft and loss of significant artworks, some with multimillion-dollar values, from Jewish families. However, the tale of the millions of Jewish-owned books looted by Adolf Hitler's forces is less well-known.

In their crusade to erase Jews and their culture, the Nazis seized books from European libraries, universities, and other public and private collections across Europe. While some were destroyed or sent to paper mills, numerous others were saved for institutions the Nazis intended for so-called scholars to "scientifically" prove Jews' supposed inferiority. Although these institutions were never built, crates of looted books were sent to sorting centers for processing, often with the help of forced Jewish labor.

Diane Mizrachi, a librarian at UCLA, was largely unaware of the looted books until 2020, when she received an unexpected email. This correspondence came from a curator at the Jewish Museum in Prague (JMP) who had been endeavoring to rebuild the collection of the Czech capital’s Jewish Religious Community Library (JRCLP), which was decimated by the Nazis.

His meticulous search through an online repository of millions of digitized books led him to believe several books at UCLA had belonged to the library. Mizrachi informed CNN that she sent the email up the chain of command, later learning about a similar request that UCLA had quietely addressed several years prior.

Mizrachi spent several months collaborating with the museum to examine the provenance of the three late-19th-century books in UCLA's collection. Eventually, six titles – including religious texts and rabbinical commentaries – were returned in a ceremony in May 2022.

“At UCLA, we have dozens of such books, and I am certain that there are many more that have not yet been discovered,” said Mizrachi. “I see it as a moral and ethical issue. Anytime something is stolen - whether it's through imperialism, colonialism, or oppressive forces - it is a wrong. It is a criminal act. Although the original owners may no longer be around, or even their heirs to return them to, their stories are crucial, and we want to preserve them.”

After the war, what remained of the JRCLP was merged into the Jewish Museum in Prague. However, with around 30,000 volumes and manuscripts looted by the Nazis, many thousands remain missing.

Michal Bušek, head of the museum’s library department, stated that the internet, the digitization of books, online auctions, and the increase in provenance research are providing the search with renewed energy.

Some 2,800 titles are still missing from Prague, according to Bušek, who informed CNN in an email. These books may be found in various university libraries, museums, second-hand bookstores, private collections, and online auctions. The recovery process, however, is not straightforward.

Bušek’s team has traced approximately 80 of the missing books so far and has had 63 returned. The museum is currently engaged in negotiations to recover the remaining volumes they have identified.

Tracing the lost books in Prague began during WWII when members of the city's then Jewish community attempted to locate some of their own volumes.

“We are continuing the efforts of our predecessors, who, in a dire situation where their own lives were at risk, worked to preserve the heritage and testimony of the Jewish presence in Bohemia and Moravia, the Czech provinces occupied by the Nazis,” said Bušek. “This library or these books is their legacy. Their story lives on. We aim to return the books to their rightful home."

Meanwhile, in neighboring Germany, organizers of a groundbreaking exhibition are hoping that it will encourage involvement from "citizen scientists - school children, students, historians, or anyone interested" in locating another group of plundered books.

“The Library of Lost Books,” a collaboration between the Leo Baeck Institute in Jerusalem and its sister organizations in the United Kingdom and the Association of the Friends of the LBI in Berlin, is both an online and physical exhibition that centers on the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies in Berlin, established in 1872 and dedicated to Jewish history, culture, and rabbinical studies.

The institute was forcibly closed under the Nazis in 1942 with some of its estimated 60,000 books destroyed and others relocated across Europe. The new exhibition features some of these looted books.

Unlike Prague's Jewish Museum, which seeks the return of the Hochschule books, the “Library of Lost Books” aims instead to create a database of their whereabouts.

“Since there is no legal successor, this is no longer a question of where these books belong,” said Irene Aue-Ben-David, director of the Leo Baeck Institute in Jerusalem.

"It's significant for us that the public gets informed about the past of these books and reports them, allowing us to preserve their history digitally. However, this isn't concerning any legal disputes."

Paraphrased text:"For us, it's crucial that people understand the historical background of these books and report them, enabling us to record their history online. Yet, this isn't related to any legal issues."

In an effort to preserve and honor the rich cultural heritage of the Jewish community, museums and institutions worldwide have initiated initiatives to recover looted artworks and books. Embracing this cause, Diane Mizrachi, a librarian at UCLA, collaborated with the Jewish Museum in Prague to return several 19th-century books that had been looted by the Nazis, highlighting the importance of acknowledging and preserving these stolen stories.

Recognizing the significance of style and arts in expressing a community's unique identity, the recovery and exhibition of these looted books serve as a testament to the resilience of the Jewish community and their unwavering commitment to preserving and upholding their cultural heritage.