This 15,800-Year-Old Carving Potentially Represents one of the Earliest Illustrations of Fishing Activities

In the final stages of the last Ice Age, an individual residing near the Rhine River in present-day Europe stumbled upon a stone and carved what seems to be a fish trapped within a net-like structure. This person would never have imagined that 15,800 years later, scholars would announce their carving as one of the earliest representations of fishing in human history.

Researchers from Durham University in England and the Leibniz Zentrum für Archäologie in Germany utilized sophisticated imaging methods to uncover a fish engraving concealed behind a grid-like arrangement on an ancient schist plaquette (a small slice of metamorphic rock). The study, published earlier this month in PLOS ONE, suggests that these grid patterns can be interpreted as symbolizing fishing nets or traps, making this artifact not only the oldest depiction of fishing in European prehistory but also the only concrete proof of how Paleolithic hunter-gatherers caught fish during this era. However, the validity of this interpretation remains debatable.

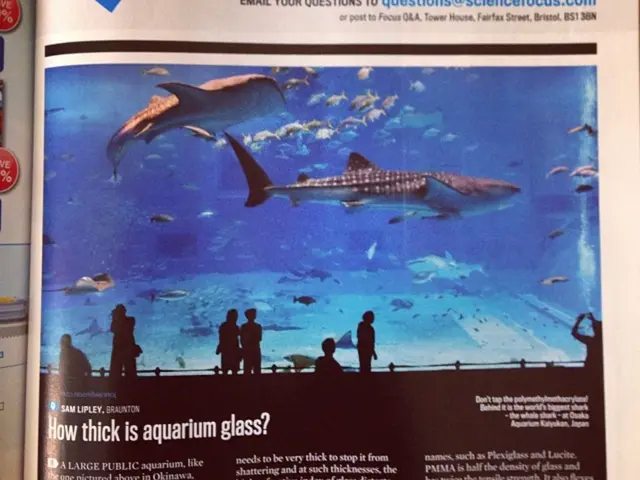

“Fish had been a part of the Paleolithic hunter-gatherers' diet at the time, but until now, there was no proof of how they captured fish,” the researchers explained in a statement from the Leibniz-Zentrum für Archäologie.

The unearthing of this fish plaquette is just one of numerous engraved plaquettes archaeologists have unearthed from Gönnersdorf, an Ice Age campsite in contemporary Germany inhabited by hunter-gatherers approximately 15,800 years ago. The etchings show stylized representations of women along with illustrations of animals essential to the survival of Late Upper Paleolithic populations (approximately 24,000 to 14,000 years ago), such as woolly rhinos, wild horses, mammoths, reindeer, and now, fish.

“This discovery provides a significant departure from earlier interpretations of the site’s iconography, which primarily emphasized more naturalistic portrayals of fauna,” the researchers wrote in the study. In essence, the presence of the presumed fishing depiction challenges the notion that Ice Age artists only presented animals and humans.

The discovery of this fish plaquette occurred during the researchers' broader investigation into the function of the Gönnersdorf plaquettes in early hunter-gatherers' lives. To accomplish this, an interdisciplinary team employed archaeology, visual psychology, and advanced imaging techniques like Reflectance Transformation Imaging, which reveals surface details invisible to the naked eye.

The researchers propose that the texture and shape of the plaquettes may have influenced what the Ice Age artists chose to depict—a process called pareidolia, involving finding meaning in an ambiguous pattern, similar to how humans perceive shapes in clouds. Moreover, they hypothesized that Late Upper Paleolithic communities might have incorporated fishing into symbolic and social activities, as per the statement.

The research team highlights that this finding serves as a reminder that just because certain technologies, like fishing nets, are seldom found in archaeological records, it does not necessarily imply they lack ancient origins. Ultimately, the Gönnersdorf fish plaquette adds to an impressive collection of Ice Age art, offers insights into our ancestors' ability to consume fish, and may even indicate that paleolithic artists derived inspiration from daily tasks.

The discovery of the fish plaquette at Gönnersdorf challenges the notion that Ice Age artists only focused on naturalistic portrayals of fauna, suggesting that technology like fishing may have played a role in their symbolic and social activities. With advanced imaging techniques, we can now see that the grid patterns on ancient artifacts like this plaquette might represent fishing nets or traps, hinting at the use of technology in the past and shaping the future understanding of our ancestors' lives.