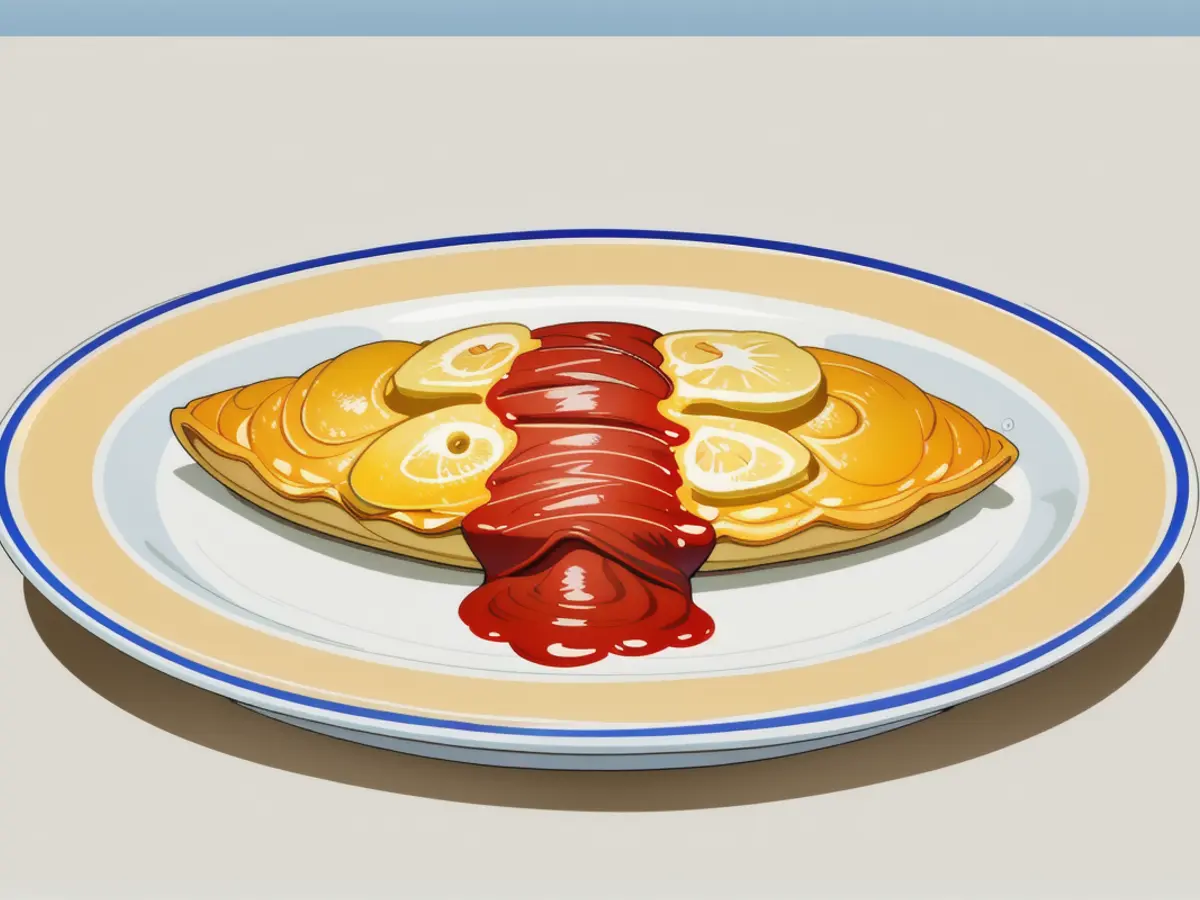

This edible delight appears excessively tantalizing, bordering on unbelievability; unfortunately, reality proves its existence.

These are "shokuhin sampuru" — authentic-looking food imitations frequently displayed outside Japanese eateries to entice diners inside. A common incident in Japan, a multitude of these replicas are showcased in London for the first time in an exhibition, as per Simon Wright, the show's curator and head of programming at Japan House London.

"Tempting Taste!" showcases replicas made by the Iwasaki Group, the pioneer in imitation food production and currently the largest manufacturer in Japan. (The company generates at least one replica every 40 minutes, according to Wright, to maintain its viability.) The company's founder, Takizo Iwasaki, reportedly gained inspiration from viewing molten wax taking the shape of a flower in a puddle as a child.

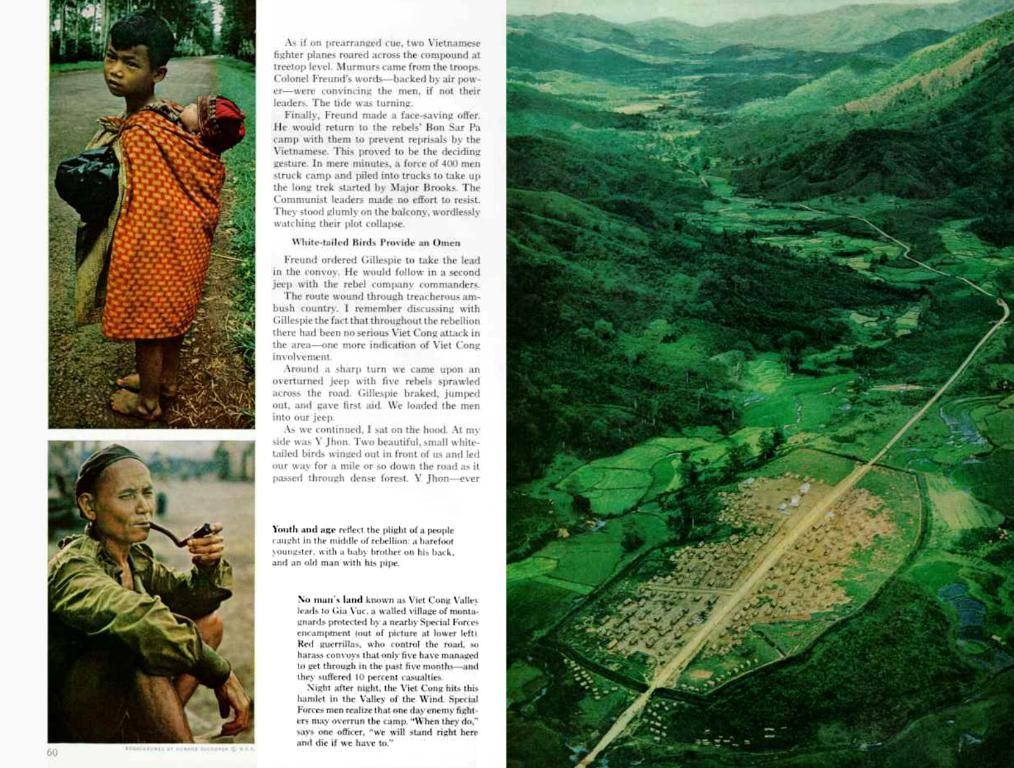

A rendition of Iwasaki's inaugural replica, representing an omelette his wife prepared, is on display, named "yearly celebration omelette." Over time, Iwasaki methodically perfected his craft, primarily using wax and agar-agar molds, though the company now primarily utilizes PVC.

Yet, the broader origin story of food replicas remains a jumble, according to Nathan Hopson, a Japanese literature professor at the University of Bergen. Hopson, who has extensively studied this topic, collaborated with CNN, suggesting a plethora of diverse beliefs about how these replicas became traditional in Japanese culture.

One extensively popular notion, per Japan House, suggests they were created to make Western dishes more familiar to a "curious yet cautious" Japanese public that would otherwise be unfamiliar with these dishes. Among the myriad of Japanese delicacies on display, the exhibition features strikingly lifelike replicas of bacon, eggs, and grilled cheese.

The exhibition's focal point is a map of Japan made entirely of food replicas, representing each of the nation's 47 prefectures. Each replica was specially requested and crafted by the Iwasaki Group, which created unique replicas of dishes for this particular event.

Choosing a single dish per prefecture was a tedious task for Wright's team, who consulted a Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries' list before also seeking input from regional residents. “You start to uncover that numerous individuals have strong opinions on this,” Wright mentioned.

An exemption was made for Hokkaido, the country's northernmost prefecture, represented by two dishes: "kaisen-don," a bowl of rice topped with seafood, and "ohaw," an Indigenous Ainu community soup. Given the Iwasaki Group had never created an ohaw replica before, the team had to obtain the dish from the community, which was then sent to Osaka, photographed, and converted into a replica the following day.

Creating the impression of truly lifelike liquids is among the most challenging aspects of replica crafting. When executed correctly, the result is bowls of soup and glasses of wine that seem to be on the verge of spilling over if handled by an intrigued visitor.

There is something "hyper-realistic" about these foods, as explained by Wright, which intentionally stimulates the memory and imagination of potential customers to pique their interest and attract them for a meal. “They are intended to grab attention instantly,” he said. “To try and draw them in for lunch or dinner.”

Fundamentally, people believe that the food they see on display will be as delicious as the real thing, with Hopson referring to them as a "promise." “I can visit any restaurant in Japan, in any town or city, and trust that I will receive the same meal,” he said.

However, replicas serve more than just marketing purposes. They originated from Shirokiya, a significant department store, which introduced them following a disastrous earthquake in Japan's mainland in 1923. Shirokiya was among the initial businesses to reopen in Tokyo, offering sustenance to the masses who could no longer prepare meals at home. Rather than choosing their order when they reached Shirokiya's top-floor café, a new system was established — customers could view the food offerings in the window while waiting in line.

“It's all about this supply-side rationalization that is an integral part of creating a new, modern, capitalist success story,” Hopson asserted, adding that they reigned supreme in the 1970s, Japan's ‘zero year’ for fast food.

Even now, these replicas are continually evolving in their purpose. The exhibition highlights their use for quality assurance in food agriculture and manufacturing, as well as nutritional purposes, by demonstrating the ideal diet for a diabetes patient.

The exhibition also invites visitors to arrange their own bento box using the replica treats. Who said you shouldn't play with your food?

"Tempting Taste" concludes on February 15. View additional images from the exhibition below.

The Iwasaki Group, known for its innovative design in food replica creation, showcases various dishes in wax, agar-agar, and now primarily PVC, aiming to replicate a dining experience's style and allure. The exhibition features replicas of Western dishes, such as bacon, eggs, and grilled cheese, which were made more familiar to the Japanese public with their striking realism.